Society of Scholarly Publishing's 2010 Annual Meeting: Sustainability and Transition

NOTE TO READER: Download the PDF to read the full article...

The main take-away from the Society for Scholarly Publishing’s (SSP’s) 2010 Annual Meeting was that this is the year “sustainability” became a bad word. Usually, you don’t see a whole conference turn against a single word. A few people in a session here or there might voice a concern, but to have what can only be described as a relentless and sustained assault across sessions, in and out of hallway and exhibit hall conversations, and across multiple days is truly remarkable. I pity the word that gets on the bad side of an SSP conference.

But what was all the fuss about really? Sustainability is such an unassuming word. It is quiet and keeps to itself. Some might say it is a bit milquetoast, but really is that cause for such hostility?

The problem is precisely its milquetoast quality. It implies that all one needs is to get by. All one needs is to break even, to come out without loss, to be no worse for wear. In short, it implies that milquetoast is OK.

And sometimes milquetoast just is not acceptable. Sometimes one needs a bit of what Joe Espisito would call reckless enthusiasm. Or at least something a bit ahead of breakeven.

The case against sustainability was first made by Geoffrey Bilder in his PowerPoint Karaoke session with Kent Anderson. What, you might ask is PowerPoint Karaoke. Here I will defer to Wikipedia:

Powerpoint-Karaoke is a spin-off from the traditional Karaoke, however instead of singing songs, the participants must present an impromptu presentation based on a random presentation, projected on a screen, to an audience.

In the case of SSP, meeting attendees were invited to submit slides to the session moderators in advance. The moderators then showed the slides to Bilder and Anderson, neither of whom had seen them before. They were then prompted to extemporaneously talk, providing their perspective on the slide

One of the slides was about sustainability. Bilder took issue with the notion that aiming to simply be sustainable was sufficient. Even not-for-profit organizations need to do more than simply sustain their business, to “grimly hold on,” as he put it. Successful organizations need to generate surpluses so that they can experiment, invest, and improve. New technologies, new publication models, new products and services all require surpluses. Moreover, attracting and retaining talented staff requires more than scraping by. Bilder suggested that all organizations, commercial and not-for-profit, need to aim for “thriving” not merely sustainability.

Implicit in Bilder’s critique, and explicit in Joe Esposito’s comments on sustainability during the closing session (the Scholarly Kitchen’s “Food Fight” was covered extensively with a link provided below), is the notion that we are in a period of transition, where the need for experimentation and new development is paramount.

This theme of transition permeated the meeting and was probably best described by John Sack during his plenary talk, Publishing in the Post-Web World. Sack made the compelling case that the transition period we are entering is very different from the one we have just gone through. Over the last 15 years we have rethought the “distribution box” for scientific and scholarly content, with most books and journals now available electronically. However, the content itself—and the formats it is produced in—have scarcely changed for scholarly publishers. We are just now beginning to rethink the rest of the box—the containers we are so familiar with, whether in electronic or print form: journals, books, articles, chapters, and even websites.

The role of publishers is to help develop, curate, and distribute knowledge in whatever formats and media it is needed, not the production of specific containers. Sack urged publishers to consider this shift as an opportunity. As the center of gravity shifts from the Web to a more diverse array of communication tools and technologies, opportunities are emerging for publishers to create new products and services that continue to add value to the scholarly communication ecosystem.

Some of these emerging areas of opportunity were explored in more detail in other sessions. This author moderated a session on scientific applications, for example. The session included a presentation from Steve Welch of the American College of Chest Physicians and SiNae Pitts from Amphetamobile on SEEK, the ACCP’s sleep medicine application for the iPhone and iPad. The interesting thing about SEEK was that much of the information in the application came from a print book. The information was updated and, in some cases, redeveloped for the new format, but the ACCP essentially jumped from a print book to a mobile application without developing a website for the content.

Keir Mierle from Google provided a demonstration in this same session on Astrometry.net. Astrometry.net is not a Google product but rather a collaborative, not-for-profit initiative that has provided both amateur and professional astronomers with a powerful new tool for identifying the position of images taken of the sky. Anyone can submit a photograph of the night sky to Astrometry.net and the site will identify the coordinates and objects in the image. It is able to do this by matching relational star positions in the image against positions of stars in its extensive database. Astonometry.net is therefore a database, search engine, reference work, and workflow tool in one—a new scientific resource outside of the traditional containers.

The discussion of mobile applications continued in another session moderated by Darrell W. Gunter of Collexis. This session included overviews by John Barker of Wolters Kluwer, Daniela Barbosa of Dow Jones, and Kim Murphy of Elsevier on the range of mobile applications offered by their respective companies. Barker described the two development paths at Wolters Kluwer. The first is a top-down approach where applications are developed via a centralized technology group. The second is a bottom-up approach whereby local offices develop narrow applications for niche (often geographically defined) audiences (e.g., architects in Germany). Barker also described how Wolters Kluwer was careful not to repeat common “shovelware” mistakes made by publishers in transitioning to the Web a decade and a half ago. By this he meant that one cannot simply shovel content developed for other purposes and formats into an application and expect it to work. Content must be carefully selected, and in some cases updated or redeveloped, for the purpose at hand.

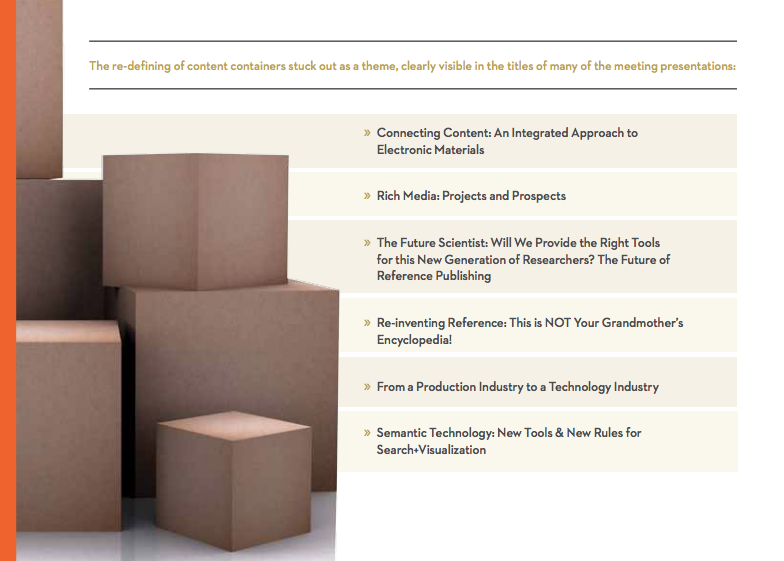

The session titles below are, to my mind, representative of the conversations, experiments, and investigations going on throughout the industry. I was unfortunately not able to attend all these sessions but look forward to catching up as they are posted on the SSP website.

One presentation I did see but will definitely revisit is Brewster Kahle’s keynote. If his presentation was perhaps a bit off-topic from the perspective of content transition, he can be excused. Kahle, founder of the Internet Archive and the Open Content Alliance, described his vision for a distributed electronic book dissemination system (Sack’s “distribution box”) that does not rely on a few proprietary mega-stores. Ebooks could be purchased, rented, “checked-out” (in the case of library copies), or freely accessed (in the case of public domain works) using a distributed content-finding system called BookServer. The idea is that a search for a book via BookServer will return all the options and the user can then select from a menu of accessing and format options (e.g., PDF, ePub, Mobi, XML, etc.).

To quote from the BookServer website:

As the audience for digital books grows, we can evolve from an environment of single devices connected to single sources into a distributed system where readers can find books from sources across the Web to read on whatever device they have. Publishers are creating digital versions of their popular books, and the library community is creating digital archives of their printed collections. BookServer is an open system to find, buy, or borrow these books, just like we use an open system to find Web sites.

The BookServer has already been built and many public domain works are now available. The question is whether BookServer will gain traction with libraries, publishers, booksellers, and book readers

The landscape for the last 15 years has been familiar. Yes, there have been revolutions in the way scholarly content is distributed but the content itself has remained fairly stable. Now we are headed into uncharted waters—blank spots on the map. What is beyond? Who is to say? The interesting thing about the future is that it is unknown. I think it is safe to say, however, that the future will bring challenges and opportunities—opportunities not merely to sustain the status quo but to thrive in an evolving information landscape.

Publication data

DOI10.3789/isqv22n3.2010.09

/sites/default/files/stories/2019-09/Clarke_SSP2010Meeting_ISQ_v22no3.pdfVolume 22, Issue 3 (Summer 2010)